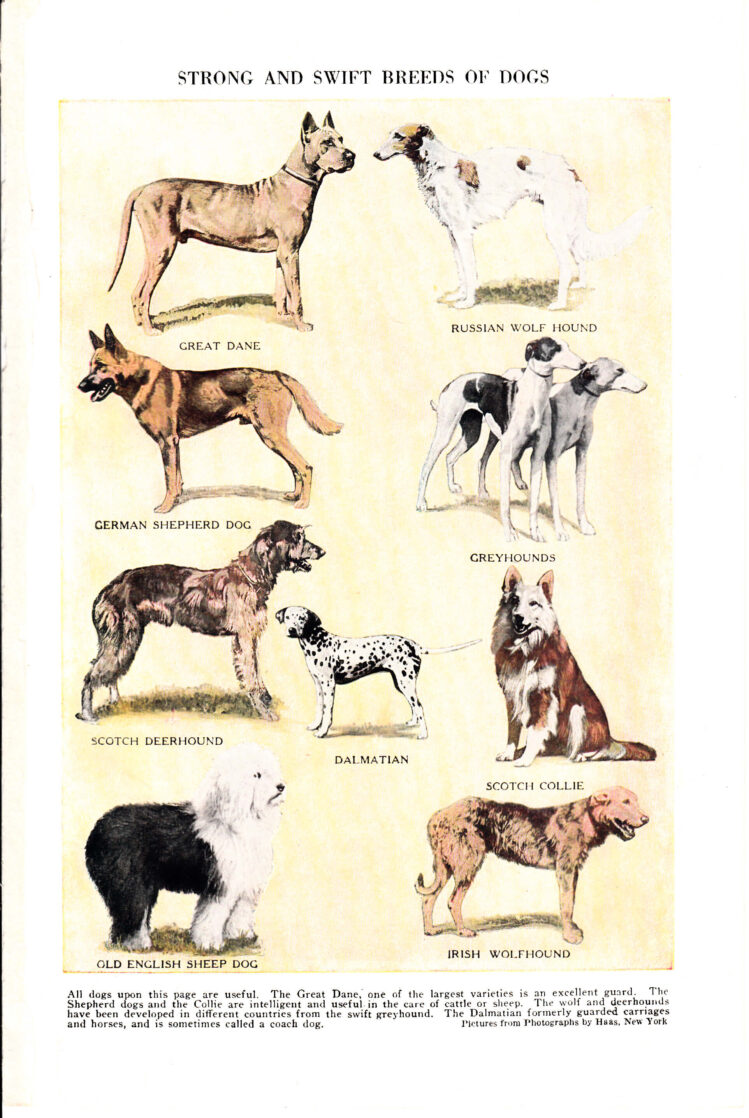

Toy Dogs

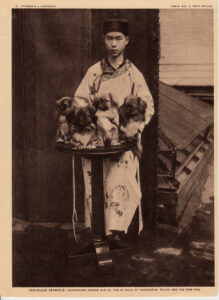

THE story of the Pekingese spaniel, recently exalted to a high place as milady’s toy, involves the names of royalty and of high military and naval dignitaries. When the Summer Palace at Peking was looted in 1860 by the English and French, the invaders found in a garden five imperial dogs that had escaped from their official

guardians, the eunuchs of the court. According to Lord John Hay’s account, he and a brother officer took all but one of the dogs, and that one was presented by General Dunne to Queen Victoria. Inquiry revealed the fact that ll the other palace dogs, or dogs of the Sacred Temple of Peking, had been taken away by the members of the court to their retreat. It is therefore reasonable to surmise that the race so widely propagated in our day owes its chief origin to these five spaniels seized as spoils of war more than a half century ago. During the Boxer Rebellion, the fact was confirmed that this breed of spaniels is especially cherished and guarded by the royal family of China, when other kinds of spaniels, pugs, and poodles, were found in the Palace by the Europeans, but no imperial dogs, they having been sent away to the refuge at Si-ganfu. A further element of interest was introduced in the story of the Pekingese when, about fifteen years ago, an English gentleman of affairs in China succeeded in having a veritable specimen of the Celestial dog smuggled out of the country in a crate that enclosed some deer that was being shipped to England. The dog was secreted in the hay provided for the deer and thus escaped detection. The coat of recognized descendants of original specimens of the breed is golden chestnut, with “trousers,” tail and feathering a paler shade, and the muzzle and tips of the ears black; the legs are bowed, the tail curled, and the eyes prominent and brilliant.

The black and white Japanese spaniel of the disdainful nose is one of several races of “sleeve dogs” bred by the people of the East. As the name indicates, it is small enough to be carried in the flowing sleeve of the Oriental. Thoroughbred specimens commonly weigh five to seven pounds, and one mite named Kara is recorded as having counted exactly as many pounds as years when two and a half years of age Macaulay is authority for the statement that Charles 11 of England liked to stride among the trees with a bevy of toy spaniels at his heels. In token of this sovereign’s fondness for the breed of spaniels petted in hi day, these small dogs, “gentle, loving and courteous to man,” bear his name. Of probable Japanese origin, they so ingratiated themselves into the hearts and tastes of the English that, in various forms and varieties, the toy spaniel was frequently pictured on canvas and loom. Van Dyck, Watteau, Francois Boucher, Greuze, and great English painters delighted to introduce this gay little dog into portraits, and fanciful representations. No other breed has been so often portrayed as the companion of ladies, children of gentle birth, and exquisites of noble station.

“The offspring of the stock of Malta,” referred to by “Theophrastus about the year 300 B. C., and described by his master, Aristotle, at a still earlier period, is said to have been in the favored lap-dog of fashionable women in the time of the Roman emperors. Not infrequently in our day proud owner of these silky little white blooms of dogdom display their diminutive form by exhibiting them in the silver cups awarded at bench shows. In size the Maltese dog resembles the Oriental spaniel, but has a more lively expression.

Before the War, visitors to Brussels remarked the prevalence of the quaint, tawny toys called Brussels griffons, which so often accompanied Belgian ladies to market on Grand’ Place, or for afternoon walks on the Avenue Louise. Forty years ago, the same game little dogs, less well groomed, perhaps, but equally popular with their masters, used to ride back and forth in the pockets of mid-England miners, and emerge at the noon hour to amuse hilarious gatherings by their alert manners and nearly human expression. In our time they have established themselves as favorites of the well-to-do.

The Pomeranian is an Arctic breed, whose ancestors lived amid the arid wastes of Siberia. From this desolate region a tribe of Samoyedes emigrated to Pomerania, now part of Russia, on the Baltic Sea. Rivaling the Pekingese in fashion at the present time, the miniature descendants of this ancient race are sprightly, intelligent and devoted. The color of coat most desirable is brown in varying shades, though wee dogs mantled in a straight coat of black, shaded sable, or orange or smoke -color, are also admired.

Besides the toy breeds mentioned in the foregoing paragraphs, the Kennel Clubs of England and America recognize as toys, black and tan terriers under seven pounds in weight, miniature bull terriers under eight pounds, poodles under fifteen inches in length, poodles under fifteen inches in length, Italian greyhounds, pugs and Yorkshire terriers.

Note: this was an article in the magazine The Mentor way back in 1918. As you can see the english word was quite different back then. But the history of dogs being much closer to their origins back then is clearer and more accurate than the information on the history of dogs being presented today.

BIG DOGS

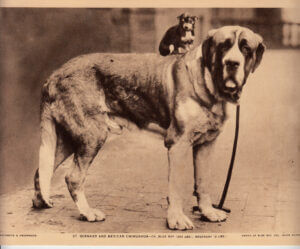

On a frequented Alpine highway between Switzerland and Italy stands the somber gray hospice named for the good Bernard de Menthon, whose statue overlooks the shelter he founded in the year 962 for the benefit of pilgrims going to Rome. The snow on this mountain road eight thousand feet above the sea is a dangerous

menace to the thousands of travelers that pass this way from September to June, and untold numbers have been saved and guided to the hospice by dogs of extraordinary scent, splendid courage, strength, and intelligence. The first dogs employed by the monks of St. Bernard came from Spain, but the blood of the Great Dane, Mastiff, native sheep-dog and Newfoundland is in the present race of St. Bernards. Only short-coated dogs are used, as the snow impedes the progress of long-haired specimens. Full-grown St. Bernards at the hospice kennels often weigh 150 pounds and stand thirty inches high at the shoulder. Their strength is sufficient to drag or carry a man for a long distance. In summer the monks teach the young dogs to search the drifts in the valleys for men who bury themselves in the snow, and in this way they are trained for rescue work. During the season of tempest and avalanche, the dogs are constantly at the call of the Brothers, of whom there are about twenty in residence at this, the second highest dwelling-place in Europe. Within recent years telephone communication has been installed between the summit of the pass and the base. When travelers leave from inns on the Swiss or Italian border, the hospice is advised. If a storm threatens o the expected travelers do not arrive in due time, the monks start down the mountain-side with their trained and willing companions. Sometimes the monks themselves are blinded by hurricane and snow and, walking the hidden brink of steep cliffs, are drawn back by the sagacious creatures at their side. On occasion, groups of dogs are sent out alone to meet toiling wayfarers and guide them to safety. The far-renowned Barry, to whom forty persons owed their lives, is commemorated by a monument near the monastery which represents him with a little girl on his back. This child he warmed to life when he found her half dead in the snow, and by his knowing pantomime succeeded in persuading her to climb on his back, and thus ride to the shelter of the welcoming hospice.

THE NEWFOUNDLAND

In Newfoundland and adjacent islands the Newfoundland dog is the sole beast of burden in certain rugged localities. He draws wood and game, and on fishing-boats large hairy dogs frequently act as retrievers of fish that fall from the deck in loading. “Most of them,” says a traveler, “boast at least a strain of that Newfoundland breed of which even a trace seems to ennoble the most outlandish of mongrels. When the master puts out to his vessel, Jacko swims after, though the distance may be upwards of a mile, and the water wintry cold.” So far has the breed deteriorated in its original habitat that when the Prince of Wales, now King George IV, visited the colony some years ago, a committee appointed t select a genuine Newfoundland dog as a gift was able only with the greatest difficulty to find one worthy of the royal guest. In England and America there are still a few dogs that elmulate Landseer’s “Distinguished Member of the Humane Society,” painted in 1838 and later chosen as the model head for a now somewhat rare Newfoundland postage stamp. Robert Burns extolled the Newfoundland in “Twa Dogs,” and to a noble member of the same species Lord Byron erected at Newstead Abbey a monument “To mark a friend’s remains….I never knew but one,” he mourned,” and here he lies.”

THE GREAT DANE AND THE MASTIFF

The Great Dane, whose history fails to disclose any relation whatsoever to Denmark, has been called “the ranking member of the dog world,” because from ancient times it has so often been portrayed at the sides of nobles and statesman. Prince, a famous Great Dane that was taken to special audience with Queen Victoria. He was said to have stood thirty-seven inches high to the top of the shoulder. Size and symmetry are the distinguishing features of this imposing breed, which is well represented in this country. In the words of an expert, the Great Dane of high degree “must show speed lines, with weight and strength.”

The antecedents of the Mastiff, like those of the Great Dane, were used in wild boar hunting in the Middle Ages. Dr. Caius, an eminent English scholar, described the mastiff of the sixteenth century as “vaste, huge, stubborn, ougly and eager.” The mastiff of modern breed was at the height of its popularity twenty years ago. Of mongrel origin, crossed with the Great Dane and the St. Bernard of old-fashioned type, specimens of the animal were exhibited at American dog shows whose weight frequently approached one hundred and forty pounds.

Published in 1918

THE HOUND FAMILY

BRAN, “the mountain torrent,” is known to readers of ancient British history as the comrade and aide of the chieftain, Final. His fame is sung for his prowess as in the hunting field, and on the field of battle. Like other dogs of Ossian, the semi-historical Gaelic bard and warrior of the third century, Bran was an Irish wolfhound, akin to the greyhound, but rough and curly-haired, and tall enough to lay his head on the shoulder of his master sitting at table. In his “History of Animals,” dogs of this renowned family are described by Oliver Goldsmith as standing four feet high. Sometimes they were protected in the hunt by “laced doublets, studded with metal points.” After the wolves of Ireland were exterminated, the wolf dog became practically extinct, but the breed has within the past fifty years been revived to some extent. The Scotch deerhound, agile but not so strong, hunted the fleet-footed denizens of the Highlands. Staghounds were first recorded in the reign of Queen Elizabeth.

Philip the Good of France (born 1396) numbered in his hunting entourage thirty superintendents and pages of the kennels, eighteen valets of the running hounds, six of the spaniels, six of small dogs, six of English dogs (mastiffs), six of Artois dogs (matins), and twelve bakers of dog bread. Some extraordinary representations of hunting hounds illustrate “The Master of Game,” that classic of medieval sport written by Edward Plantaganet, second Duke of York, between the years 1406 and 1413.

In this manner the younger Xenophon commemorated his good greyhound; “I have myself bred a swift, hard-working, courageous, sound-footed dog, most gentle and kindly affectioned, and never before had I such a dog. When not actually engaged in coursing, he is never far away from me, and he has many different sorts of speech…Now, really I do not think I ought to be ashamed to chronicle the name of this dog, or to let posterity know that Xenophon the Athenian had a greyhound called Horme, possessed of the greatest speed, and intelligence, and fidelity, and excellent in every point.”

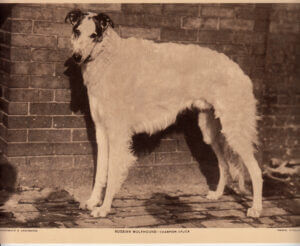

The Italian greyhound, diminutive and delicate in type, frequently appears in pictures of royalty, and has a fascinating story all its own. The Russian wolfhound, a shaggy, swift-footed and picturesque breed, is described as “the noblest-looking as well as the newest addition to our bench of sporting hounds. Like its Irish prototype, it bears a great affinity to the greyhound. Except for its fleecy coat and feathered tail, it is practically built on greyhound lines with certain modifications. The veriest tyro, having once seen it, can recognize a borzoi head, with its thin, narrow Roman-nosed contour, and its long, fine muzzle. The grip of these hounds is far in excess of what one would give them credit for, and the boast of their masters in their native land is that we have no hound so tenacious of holding on to its quarry.

Izaak Walton avows his love for the music of a pack of dogs. The foxhound and the harrier, the otterhound and the beagle have no physical relation to breeds of hounds afore-mentioned, but are all part of English sporting tradition. The name “beagle” appeared over four hundred years ago in literature. A plaything of court ladies, this small hound is said to have fitted into a knight’s gauntlet – “its voice was so small compared with that of foxhounds that another name for them was ‘singing beagles,’ and efforts were made to get voices of different tones to chime melodiously.” Since Colonial days the beagle has received the favorable attention of American huntsmen, many noted packs having been maintained in the South and East. Packs of English foxhounds are sometimes unsuccessful in this country, because of geographical conditions, and similarly American trained dogs may fail on English soil.

Like the long-bodied, short-legged basset hound of France, the badgerhound, or dachshund, is an abnormal type of hunting dog. James Watson describes the basset as a large badger-hound with a head resembling a bloodhound. In the days of the Scottish kings, bloodhounds, also called sleuth hounds, were kept on the Border to track fugitives. History says that Robert Bruce was repeatedly tracked by such dogs, and on one occasion escaped by wading in a brook, thus throwing his pursuers of the scent. Landseer painted the bloodhound of his time-a representative of the breed that had a lower skull, a less pronounced “wrinkle,” and shorter flews than the dog that breeders prize today.

Published 1918

THE TERRIERS

The terrier derives its name from terra (earth), and “denotes a variety of dog remarkable for the eagerness and courage with which it attacks all quadrupeds from the fox to the rat.” Terrier are classed as smooth and rough-haired, and originated in Great Britain and Ireland. Dr. Caius, in 1565, described them as “Terrars, which creepe into the ground, and by that means make afrayde.” For many years, as dog styles go, the most popular member of the breed was the smooth-coated fox terrier–strong, lively, swift, enduring, symmetrical in body, active in mind, and a rare dog as a pet. The wire-haired fox terrier has of late superseded its cousin in the favor of fanciers. Old prints and paintings corroborate the statement that the former is of the more remote origin. The famous sire, Meersbrook Bristles, imported from England twenty years ago, had a progeny so distinguished and true to family tradition that he is credited with having changed the type of the wire-haired terrier in America. According to present-day standards, this species “should resemble the smooth sort in every respect except the coat. The harder and more wiry the texture of the coat is, the better.” The head of the wire-haired fox terrier is classed as finer than that of its smooth-haired prototype.

The Airedale terrier has as ancestors a rough terrier of Yorkshire, the pugnacious bull terrier, and the otterhound. Developed by the mill-hands of Aire for fighting and poaching, the breed finally came into favor for qualities other than those of a gamester and marauder. Since 1898 this dog has been conspicuous at Canadian and American shows. “What a dog can do, an Airedale can do it, says his champions. “Very sensible and intelligent; will retrieve on land or water; excellent in driving cattle, and kill vermin against any other breed of dog; game as a pebble, and first-rate guard–the best all-round dog living, and no one could get a better companion.” Rolf, the wonder-dog of Mannheim, whose intellectual achievements have so mystified psychologists, is an Airedale.

The Yorkshire terrier is named for the country of England where the type was developed from a work-a-day cross-bred dog to an aristocrat with a remarkably long, straight, steel-blue coat of silky hair.

Irish terriers have a distinctive head and a “keen, varminty expression.” “When ‘off duty,'” says an admirer, “they are characterized by a quiet, caress-inviting appearance, and when one sees them endearingly and timidly pushing their heads into their masters’ hands, it is difficult to realize that at the ‘set-on’ they can prove they have the courage of a lion, and will fight to the last breath in their bodies.”

The bull terrier has been classed as an individual breed for nearly a century. “The wisest dog I eve had,” wrote Sir Walter Scott, “was what is called a Bull-dog Terrier, like the white English terrier, is of British, not American, origin, though American-bred dogs of this class now more than hold their own with the best of those sired across the water. Essential marks of thoroughbreds are the high, pointed ears, the oblique set of the small wise eyes, and the all-white coat. Possessed of the determination of the bull-dog and the activity and aggression of the terrier, they have renown as fighters, and only their special champions praise their dispositions.

Sir Walter Scott betrayed his love for all dogs in his devotion to Camp, Maida, Hamlet, Finette, and a gallant crew bred in his imagination. “Dandie Dinmont,” James Douglas in life, was the owner of Mustard and Pepper, two game little terriers to whose descendants the name of the old border farmer in “Guy Mannering” was applied by Scott. The bright dark eyes of the Dandie Dinmont, like those of the Skye and some other long-haired terriers, are veiled by an overhanging fringe of hair that gives them a somewhat impish appearance. Poodles from wrecked ships of the Spanish Armada, crossed with British dogs, produced the skye terrier. The shrewd, long-bodied Scotish, Scottish, West Highland and Welsh terriers found wide acceptance in America.

The companionable Boston terrier, whose popularity never wanes, is a comparatively recent American product. Its progenitors were the brindle bull-dog and bull terrier. A club of Bostonians was formed twenty years ago to secure recognition for the breed, and thus it got its name.

Publish 1918

DOGS THAT SERVE

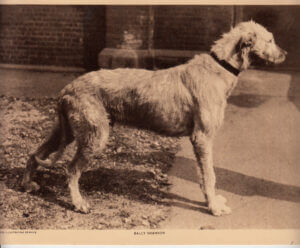

The MENTOR is fortunate in being able to reproduce the picture of a hero of heroes, one that has proved twice over the valiant stuff that dogs are made of. Bally Shannon, an Irish wolfhound, was taken by a British officer into the trenches, and served there as a Red Cross dog until wounded in the left shoulder by a shell.

His master was also wounded, and together they were invalided home. Crossing the English channel, the hospital ship on which they rode was torpedoed in the night. The officer and two others found refuge on a piece of wreckage, but there was no room for Ball Shannon, and his great weight would have submerged the others. When he attempted to get aboard the floating timbers, his master warned him back with a gentle word of explanation. And Bally understood. Thereafter he made no effort to climb out of the icy waters; only when he grew over-weary he came close and rested his shaggy head and fore-paws on the edge of the improvised raft until he had strength to go on paddling about in the dark and the cold. At daylight they were saved, and later the dog and his master came to America to recuperate from wounds and exposure. Since then, though not fully recovered, Bally has again been a dog of service, helping the shepherd in Central Park, New York, to guard the sheep that crop the grass–tame work enough after succoring wounded soldiers on the battle-field. But his friends hope a life among peaceful surroundings will some day soften the sorrow of his war-troubled eyes.

The dogs of Alaska, says Belmore Browne, “make the northern world go round.” They haul men and freight from one end of the year to the other, they are the mail carriers over ice and snow, and they bear packs sometimes weighing forty pounds, containing the stores and implements of miners and explorers. The malamutes, huskies and Esquimo dogs of northern regions are sometimes of pure strain, but, running free in Indian villages and in distant camps, most of them boast the blood of a variety of breeds. Often one sees specimens half or one-quarter wolf that bring to mind valiant episodes in Jack London’s “Call of the Wild” and “White Fang.” Among hundreds of Alaskan dogs that have gone overseas to do duty with the allies in France, several have received gold collars, war medals and other decorations for the faithful accomplishment of hazardous errands.

In Thibet and the Pyrenees there are species of herding dogs quite distinct from those bred in Scotland. The Book of Job mentions dogs that watched sheep on the hills centuries before the Christian Era. “There is no breed,” says a lover of the sheep-dog, “with such a wise look as the collie.” Burns called him a “gash (wise) and faithful tyke,” whose “honest, sonsie, bawsn’t (taking, white-streaked) face aye gat him friends in ilka place.” In the words of a good judge of dogs, “there is not a more graceful and physically beautiful dog to be seen than the show collie of the present period. His comeliness will always win for him many admiring friends.” But as a sheep-tender this aristocrat with the long, narrow nose and mantle of superb color, weight and texture, would be scorned by a Highland flock-master, whose strong-limbed dog, hardened in service, and wise with the wisdom of generations of his calling, can do work that otherwise would require the combined efforts of a dozen or more men. “Without the shepherd’s dog, wrote “the Ettrick sheperd,” “the whole of the open mountainous land of Scotland would not be worth a sixpence.”

It is said that the tails of old English sheep-dogs were originally docked by the owners because as assistants to Man in his labors they were exempt from taxation, and the herders determined this method of distinguishing them from idle pets.

“Police dogs,” on the authority of Sergent Jager, author of “Scout, Red Cross and Army Dogs,” “were first tried out in the city of Ghent, Belgium. When the movement developed in other countries, the first step toward improvement was to find the most suitable dog for the work. After a number years of experimenting, the breeds simmered down to the (then so-called) shepherd dog of Germany, the Belgian sheep-dog, the Doberman terrier and the Airedale.” To a great extent these are the types that are on duty with the armies of the World War, and all have specific qualities that fit them for service of immeasurable value.

Published in !918